Dorothy and I have combined our thoughts on the tools we feel we will utilize in the construction of our Keene site. Below is a link to view our project contract that will act as working document and guide towards our final product.

Newspapers: Online Archival Research

This article which mentions Abenaki Tribe in Vermont, dated January 29th 2018, shows an active conflict and consequence stance that the Abenaki are still facing even in these present times.

A mural called “Everyone Loves a Parade” depicting the people of Vermont, whom are all white, sparked controversy among the Abenaki of the area. Activist, Albert Petrarca, protested against mural and spray painted the words “Off the wall” on the identification plaque.

Councilor, Ali Dieng, has condemned the mural as racist and others have taken up the stance against it. Deeming it a white supremacist symbol. He has stated that “…it does not depict members of the Abenaki tribe, people with disabilities, the gay and lesbian communities, or the 14 percent nonwhite student body of Burlington schools.”

Amendments to the mural, whether to remove it or to create a new or additional piece of art are yet to be discussed.

https://www.sevendaysvt.com/OffMessage/archives/2018/01/29/burlington-city-council-to-consider-options-for-downtown-mural#.W83r0c_4NGc.email

Town Myth

To understand the history of the land that Keene State College sits on, we first have to understand the land from Native Americans point of view. We do this by looking at the misinterpretation of who, what, when, where, and why and seek how these concepts affected the Native Americans of this area. I mention the misinterpretation first and foremost because it is this precise misunderstanding that has caused the demise of the Abenaki to become forgotten and all but missing in New Hampshire’s history books. We also take in oral history, gather reading references and documents that reflect the Native and colonist’s viewpoint, and collectively combine what we have learned of the local Native Americans with that of what we’ve amassed throughout the semester thus far.

Below I mention two local myths and then provide a rebuttal, or a reply if you would, to that myth in the hopes of shedding light on a more accurate account of the events that happened during that time.

Myth: The Native Americans that inhabited the area left before the arrival of the colonists.

Reply: This myth is false. In fact, it’s documented in The Historical Society of Cheshire County that pre-1650 the Squakeag Indian culture (a common mispronunciation and misspelling of the Sokwaki Indians) “were intact and inhabiting the Connecticut and Ashuelot River valleys.” It is this frequent misspelling of Native American surnames by the colonists and receiving new surnames that were easier for the colonists to pronounce that has led to the Abenaki populace to “disappear” from New Hampshire’s historical records, as you will see in my second myth.

What I’ve discovered is that the first Native Americans in the area were known locally as the Ashuelot Indians. The Ashuelot Indians are better known as the Abenaki who belong to the Wabanaki Confederacy. This group did not leave collectively, however, upon or before the arrival of the colonists. Author, Gordon Day, points out that the Abenaki often traveled to numerous locals based on the changes in the season. Warmer, summer days would bring them closer to the coast and while colder, winter months would push them inland as they sought shelter from the cold.

So although it may seem to the colonists that the Abenaki fled before initial contact, there are more documents to prove other wise. Yet these documents are not readily known and discussed.

Myth: The Native Americans never returned to this land after the arrival of the colonists.

Reply: Also false. Keene’s Native American community didn’t vanish, as myth would have you believe. Some hid in plain sight. Many died from colonist-host diseases and wars, some unfortunately enslaved, and others “disappeared” by marrying into colonists families. Even having done so, they were faced with extreme adversity of their cultural background and forced to hide or move. By hiding in plain sight, the Abenaki had to neglect who they were as a people and assimilate to the colonist life style. They couldn’t practice their Native American traditions or speak their native language. It is believed that eugenics was practiced at this time, as well, in order to rid the colonist population of Native American bloodline as a result of these inter-racial marriages.

As a side note, I want to mention that The Abenaki would later separate into two entities when one group migrated to Canada (Western Abenaki) and the other half migrated to Maine (Eastern Abenaki.) Ashuelot River was more than a just a river for the Abenaki. When translated, Ashuelot means “land between place”. It referred to the flat land between mountains, a well-traveled route to points south, an identifier, and a meeting place. The importance of the Ashuelot can be seen as the length and demography of the river determined how it would later be divided and labeled by the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1733. They devised two townships alongside the river, Upper and Lower Ashuelot (now known as modern day Keene and Swanzey.)

We can conclude that the town myths mentioned above have been fairly debunked and scholarly fact checked by my sources cited below.

Sources

Day, Gordon M, et al. In Search of New England’s Native Past: Selected Essays. U of Massachusetts P, 1998.

Griffin, Simon G, et al. A History of the Town of Keene from 1732: When the Township Was Granted by Massachusetts, to 1874, When It Became a City. Sentinel Print. Co, 1904.

A History of West Hill-Keene, N.H: By Rich Grumbine, Antioch/New England Graduate School, Horatio Colony Trust Project, December 1987

Bruhac, M (2006). Abenakis at Ashuelot: The Sadoques Family and Keene. Historical Society of Cheshire County Newsletter, 22 (2), Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/anthro_papers/150

Oral history of The Abenaki as shared by Anita Weldon, curator of the Horatio Colony Museum.

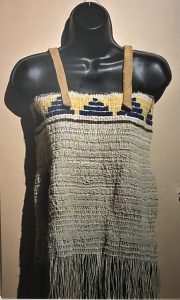

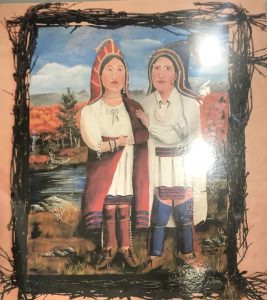

Native Artifact: The Evolution of Abenaki Clothing.

White linen French style shirts and chemises were commonplace. Abenaki crafts people usually fashioned clothing from red and blue wool. Wool hoods, wrap skirts, leggings and breech cloths were decorated with silk ribbon. Abenaki’s wore match coats (blankets) to keep warm. Finger woven sashes (belts) and leg ties (garters) were made from yarn.

Ornamentation’s were an important addition to clothing. The Abenaki wore silver or brass nose rings and ear ornaments. European trade goods were strung into everyday wear. European glass wampum beads were strung and worn much as costume jewelry is worn today. They also wore European trade silver pieces such as nose rings, arm bands, wrist bands and earrings. With so many new items available, Abenaki men still wore white shell “moons” at the breast.

18th Century European influences of dress and attire on the Abenaki women inspired them to weave hoods to imitate the French women colonists. This practice was commonly used when an Abenaki women came of age.

Sources

Horatio Colony House Museum & Nature Preserve; exhibit and oral history hosted by museum director Anita Weldon.

“Alnobak: Wearing Our Heritage Exhibit” co-curated by Vera Longtoe Sheehan and Eloise Bell, presented in partnership with the Vermont Abenaki Artists Association and Lake Champlain Maritime Museum.

A Brief Look into Western Abenakis Timeline

This timeline is but a peek into the lives of the Western Abenaki during and after the first settlers arrived. Very little is documented on them as their interior location prevented encounters with the earliest explorers. Also, misidentifying the Western Abenaki as other nations and tribes such as Mahicans or Loups led to them moving through New England History under the guise of another tribe.

It is my hope that this brief but insightful timeline can shed light onto these nomadic peoples and open the doors of curiosity as to who they really were.

Scavenger Hunt

This is the link to the scavenger we partook in. https://docs.google.com/file/d/1YCh644paZbMz6p4hfuRHgDUqvTXSJwNZ/edit?usp=docslist_api&filetype=msword

I found this scavenger hunt overwhelming and trivial. When I first heard that we were doing a scavenger hunt, my immediate thoughts shot me back to my childhood days of looking for clues that would lead me to items that would lead me to solving the scavenger hunt and eventually winning it. If this was a college student attempt at it, I would’ve rather sit it out.

As my campus partner and I perused the contents of the scavenger hunt and tried to digest the amount of information that was being asked of, I quickly realized that this was not going to be easy-peasy-lemon squeezy.

I was unable to accomplish all of the tasks. Not for lack of effort or motivation but simply because life happens and my duties outside of the classroom are unceasing.

I should mention that being a mom of two rambunctious elementary kids, a wife, and an obligation to the Army pulls me in various directions at random moments. So time management is a skill I’m constantly building on. And technology has never been an acquaintance of mine. So I ask for you to bear with me as I work through all this wizardry that is high tech.

Nevertheless, I’ve added my google docs link so you can read all the enthralling details of my plight with this scavenger hunt.

Enjoy!

Hidden pasts name of Contoocook

Welcome to Hidden Pasts Site: Contoocook derives from the Western Abenaki word meaning ‘at nut river’. The name is most likely attributed to the butternut tree that is abundant in southern New Hampshire.

Abenaki is the name of the regional natives that formerly inhabited this area of New Hampshire. They belong to the Wabanaki Confederacy.

It was fairly easy for me to attain this photo because I have to travel a lot towards Boston due to my military obligations and I often come across this city during my commutes. Once there, the views are scenic and there’s a multitude of recreational activities to partake in.