On this page, we describe who the Western Abenaki were and include an impression of their migration patterns due to seasonal changes. We also include clothing artifacts of the Western Abenaki clothing, pre- and post-colonial contact. So keep scrolling down to discover more about the Western Abenaki.

To understand who the Sokoki of the Ashuelot River watershed were, we need to understand who the Abenaki people of the New England territory were.

Abenakis are sometimes referred to as Dawnland People because the they are a tribal band that descend from the Wabanaki Confederation. Wabanaki translates to People of the Dawn.

Abenakis can be classified into two categories: the Western and Eastern Abenaki. Historically the Western Abenaki lived in what is today known as Eastern New York, Northern Massachusetts, Southwestern Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire and north toward Quebec, Canada. As members of the Seven Nations and Wabanaki Confederacy, Abenakis interacted with their Native American neighbors to the North, South, East and West on a regular basis.

Upon the arrival of Europeans, disease and warfare caused immeasurable changes in the Abenaki way of life. The Abenakis allied with the French whom they traded raw materials for new commodities such as wool, linen shirts, silk ribbons, glass beads, tools and firearms. As allies, the Abenaki and French fought together against the British encroachment into the land.

By the late 18th century, prejudice and embattled situations in surrounding areas forced the Abenaki to break up into smaller family bands or clans in order to survive. In the 18th century, the British burned down long standing Abenaki villages of Mission des Loups at the Koas, Missisquoi along the Missisquoi River and St. Francis, which the Abenaki people know as Odanak in Quebec.

Little is recorded of the Abenaki in historical accounts during the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. However, Abenaki descendants have maintained oral histories and strong traditions from this time. Since the 1970’s, the Abenaki have been experiencing an interest in cultural revitalization.

Today there are two provincially recognized Western Abenaki tribes in Canada: Odanak and Wolinak. In the United States four Abenaki tribes received State recognition in Vermont in 2011 and 2012: the Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi and Nulhegan tribes.

It is estimated that there are 2,100 Abenaki in Quebec and 3,200in Vermont and New Hampshire. This is a conservative figure as it does not include non-recognized and unaffiliated Abenaki families.

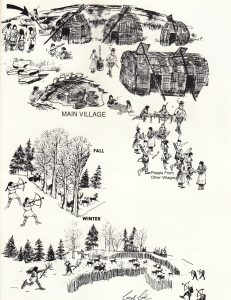

Nomadic Patterns of the Western Abenaki

During our studies we discovered that colonial history would tell of vast empty lands when first arriving in New Hampshire but what we learned was the nomadic patterns of the Western Abenaki was dependent on the season. In this following passage, we take a glimpse at the infrastructure and economic history of the Western Abenaki.

Esther K. & David P. Braun

The First People of the Northeast

Illustrations by Carole Cote

Lincoln, MA: Lincoln Historical Society, 1994

Courtesy of Lincoln Historical Society

Esther K. & David P. Braun

The First People of the Northeast

Illustrations by Carole Cote

Lincoln, MA: Lincoln Historical Society, 1994

Courtesy of Lincoln Historical Society

The Western Abenaki people needed to move around to wherever the most plentiful food sources were during each season. Their diet depended on the life cycles of other species.

Generally, fish were easier to catch in spring during the spawning season. In the warmer months of late summer, leafy plants, berries, fruits, nuts and seeds were plentiful; more meat was consumed in colder months. Living this way required specific knowledge locations of the best food source.

In the area that became New England, Native people lived in small villages. The size and location changed seasonally. During spring spawning, groups moved to the best rapids and waterfalls; in summer, many villages of more southern New England tribes could be found in clearings along river banks and meadows where land could be cultivated for crops. When fall arrived they moved to hunting grounds. In northern areas people tended to be hunter/gatherers because the climate was not conducive to crops.

John White

Indian Village of Poemiooc

Watercolor 1585-1586

Trustees of the British Museum

By using natural resources where and when they were most abundant, the Western Abenaki made sure no single species was overused or depleted. Ecological diversity ensured they had enough to be kept fed and comfortable.

Because mobility was crucial to this lifestyle, Western Abenaki dwellings were designed to assemble and disassemble easily. Called ‘wigwams’, they had bent sapling frames and were covered in bark slabs or grass mats. These were often summer houses for one or two families. Longhouses were used more for winter, housing several families. Both dwelling types would have a hole in the roof for fire smoke to escape. Raised platforms covered in mats and furs were used for sleeping.

Wigwams. Courtesy of Eastman, Seth. Winnebago family. Seth Eastman (1808-75) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, 1652, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Winnebago_wigwam.jpg. Accessed 2008.

Longhouse. Courtesy of Gordy, Wilbur F. An Iroquois longhouse. Photo . Gordy, Wilbur F. Stories of American History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913. Page 20, 1913, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theiroquoislonghouse.png. Accessed 2009.

Native Artifact

Below we’ve attached a class assignment of the few Native artifacts that we found pertaining to the Abenaki. We hope you enjoy perusing this article as it was discovering, collecting, and creating it.

Native Artifact: The Evolution of Abenaki Clothing.

“