Click on the images for a closer look.

Russia’s presence in California lasted only 32 years: from the first buildings erected in Bodega Bay to the sale of the Ross settlement to John Sutter. Russia had been trapping sea otter in Alaska, primarily to trade in Asia, for roughly 50 years before venturing south to California (Lightfoot 2005). Otter populations in Alaska fell as they were over hunted and the agrarian possibilities as well as a robust otter population made California irresistible.

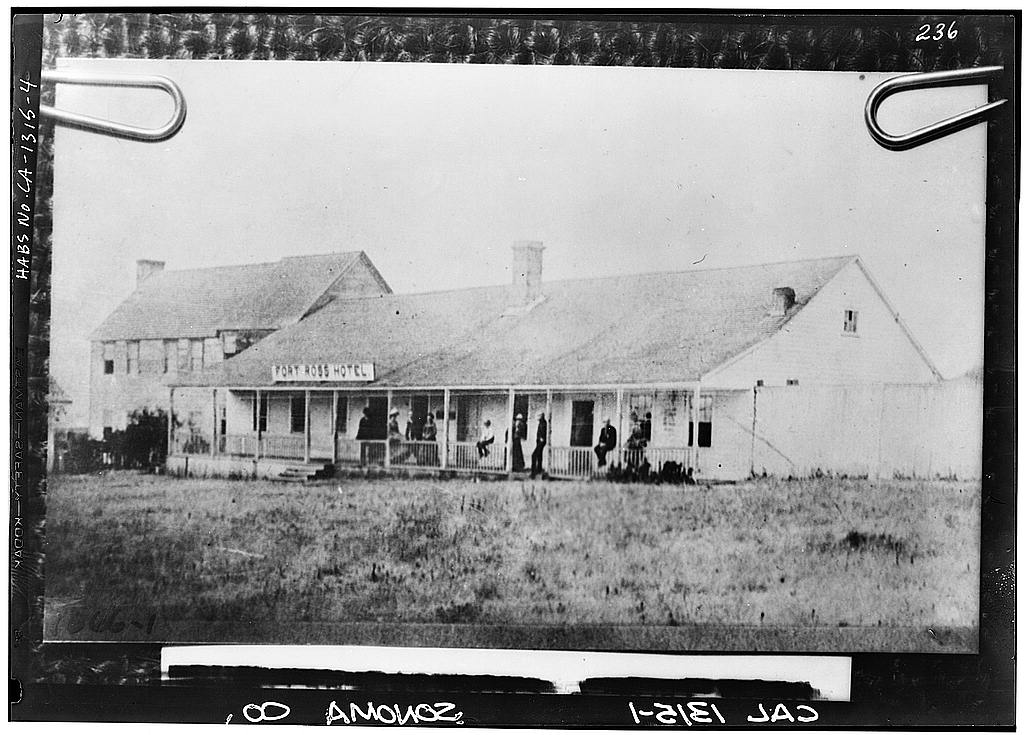

In 1806 a group of Russians, led by a high ranking official, voyaged to San Francisco Bay in the hopes of establishing a trading relationship with Spain (fortross.org). Although the Spanish were disinclined to engage in trade with the Russians whom they perceived as threats, when leadership of the area transitioned to Mexico, they were happy to sell provisions. Fort Ross was established in 1812, roughly 90 miles north of San Francisco, as an agricultural and trapping outpost, as well as a local base for otter trapping operations on the Farallon Islands. Ranches in the Bodega Bay area as well as along the Russian River were also established during this time (Lightfoot 2005).

The relationship between the Russians and the Kashaya Pomo and Bodega Miwok appears to have been less violent than Spanish or Mexican relationships with Native Californians (Lightfoot 2005) but this is not to say that it did not come without cost. A smallpox epidemic brought by the Russians may have killed as many as 10,000 Native Californians as a result of contact at Fort Ross (Madley 2016). The Russians were not interested in converting Indians, although some Pomo who lived at Fort Ross did appear to convert to the Russian Orthodox church, nor were they interested in stripping them of their culture or lifeways.

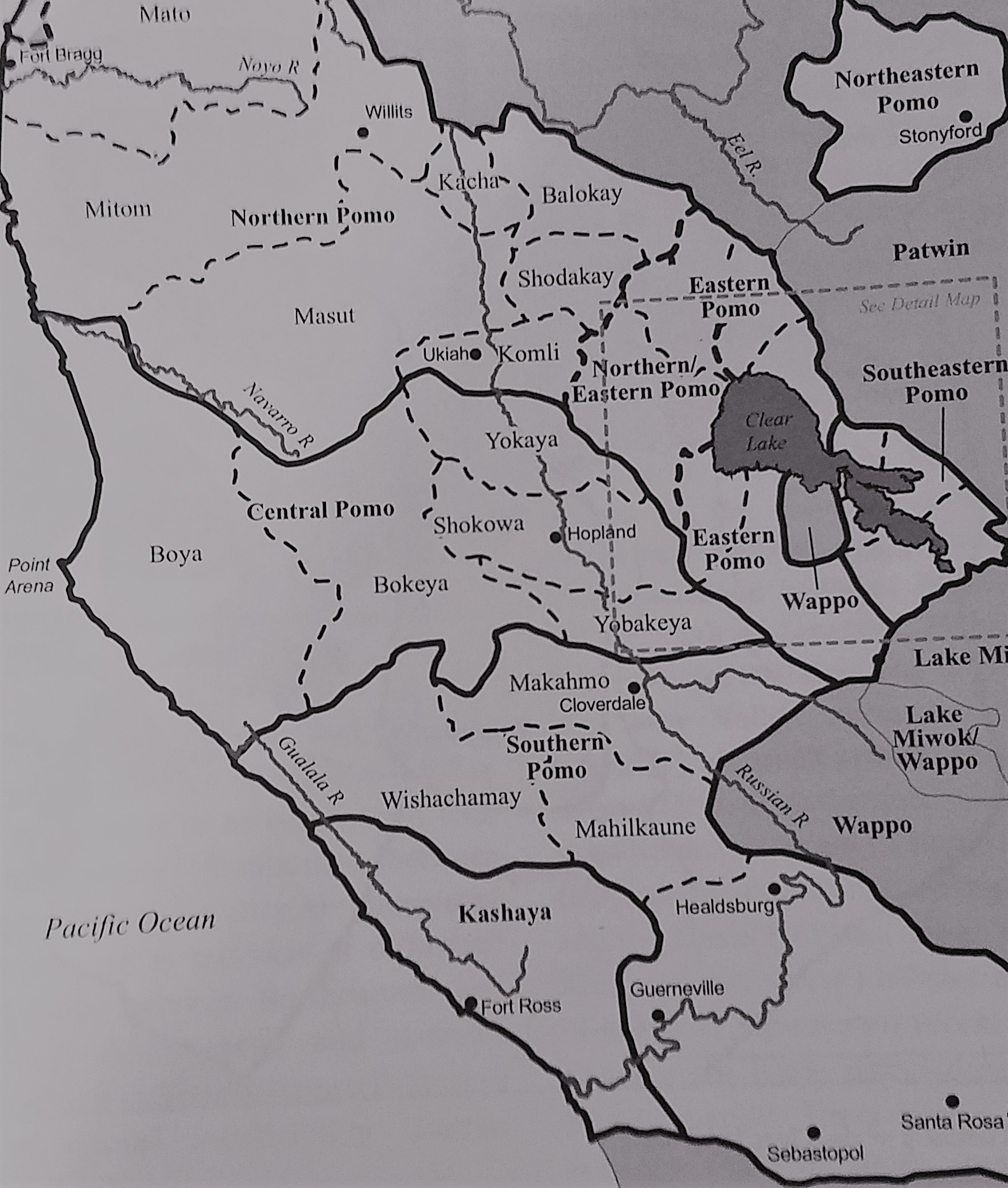

The map on the left gives a visual to help place where Fort Ross is and the native territories surrounding it.

Kashaya Pomo and, to a lesser extent, Bodega Miwok, provided a workforce for Colony Ross and were divided into four categories: prisoners, employees, seasonal laborers, and spouses (Lightfoot 2005). Prisoners were brought from Alaskan outposts to California and new prisoners were collected from local tribes as they committed offenses against Russian trappers. Prisoners were forced to build some of the structures at the Fort and other demanding physical labor but most of the workforce at Fort Ross were seasonal laborers who were paid in food, beads, tobacco, or clothing (Lightfoot 2005).

The Miwok and Pomo laborers, while sometimes abused by the Russians, were more able than Mission Indians to retreat to their home territory and retained more of their traditional culture even when living in close proximity to Fort Ross; this may explain why there were few episodes of violence or revolt against the Russians (Lightfoot 2005).