Growing up in Sonoma County I heard about Native Americans who lived in the hills surrounding my town, but the stories were always vague and unrelatable. When we studied California history in fourth grade we toured a model Miwok village. I was fascinated by it, surprised that I had never considered acorns to be edible, but the Coast Miwok people remained an abstract idea that was largely intangible to me: what I saw around me began with the Spanish and progressed from there. On another school field trip I ate fruit off of a tree planted at General Vallejo’s house, I saw where his children slept. I toured the barracks where Mexican soldiers lived, just across the street from a commemoration of the Bear Flag Revolt. These were real, tangible, fathomable. As a kid, the feeling I had was that the Indians had just been erased and only existed in stories. Doing the research for this assignment the outcome was a little better, but it still depends on where you look.

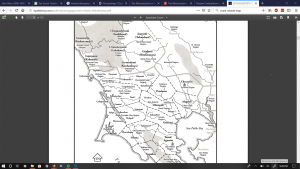

According to the Cotati Historical Society as well as the Rohnert Park Historical Society, the Coast Miwok tribe of Kota’te lived in the southern Santa Rosa valley, peacefully, with an abundance of wild foods at their disposal. RPHS claims that Kota’te was the name of a Miwok chief and that the tribe referred to the rolling hills as “Lomas de Kotate.” Both sources address the first attempted settlement of Cotati by John Reed whose crops were burned, prompting him to settle elsewhere. With the Russian presence on the north coast of California, Mexican-run missions expanded to as far north as Sonoma and General Vallejo was charged with providing military support to keep the Russians from spreading further south. As far as the Kotate go, that’s it. They were placed in missions or died as a result of the introduction of pathogens they had no immunity to.

I spoke to a friend who is a class teacher in a local Waldorf school. In their curriculum the class spent third grade learning about how Native Americans lived in the area: what their relationship to the land was and how they used it. They studied mythology, land use, and ways of life. In fourth grade they studied California history and the transference of land including the subjugation, exploitation, and genocide of local Indians. She emphasized that the lack of common languages among tribes inhibited their ability to work together against the Spanish, and with weakened numbers they were incapable of defending against gold rush settlers and the violence they brought with them. She said that although they did spend a fair amount of time on contact she tried hard to make sure the picture was balanced even though there is so much more documentation from the colonizers point of view, and she refused to do the “Mission project” which is, or was, a standard assignment for fourth graders. Instead, she told stories about how antithetical European ideas of ownership were to Native Americans. As members of a foraging economy, their reliance on the land was total and they had built in to their belief systems ways of balancing use. The Spanish defied all of the laws and moral codes that Indians followed, but somehow the Spanish weren’t the ones who suffered–they did.

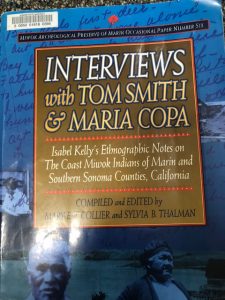

Shante and I visited the Cotati Historical Society recently to see what they had in their collection regarding the “Kotate”. Apart from a mortar and pestle on loan from Sonoma State and a couple of books of local mythology, they didn’t have much. Inside City Hall, however, was an exhibit donated by Graton Rancheria which highlighted local foodways and cultural traditions including a timeline of contact. They note that although the myth is that Kotate was a Coast Miwok chief, there is no known chief of that name–nor did the Miwok actually recognize chiefs. The narrative that the Graton Rancheria promotes is one of resilience and continuity of cultural traditions with a direct line from pre-contact to today. Although genocide, exploitation, and dispossession are important aspects of the history of local Indians, they are not defined by those and they continue to work to preserve their cultural heritage as well as funding programs such as TANF–Tribal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.