This is a guide to making maps in three different ways. The simplest way to put a google map into a post is to embed it. The second it so use Google My Maps, which lets you create markers and legend. The third is Storymap JS, which lets you tell a story about moving across a landscape.

Embedding a Google Map: Pull up any Google map, then get the embed code from Google by doing “share,” and then clicking on the embed tab behind the link tab. Then copy the embed html code and put it in the post–but you have to click on the text tab before you paste the embed code–same as with the timeline pluggin we used before. So now I’m gonna give that a try. This should show a map I made following Gordon Day 1998 about the boundaries of Sokoki land–Sokoki being the word he uses for what others call the Western Abenaki.

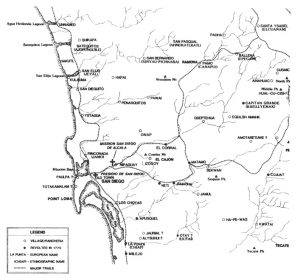

Markers and Legend into Map: My next goal was to make a map that illustrated locations in the 1640-1665 period of conflict between the Iroquois (Haudenasonee) and the Huron, who were allied with the French. The Huron in modern Ontario were selling fur to the French at Quebec. The Iroquois were selling fur to the Dutch at Fort Orange (Albany). For this I used the “my maps” option on Google, following a tutorial recommended by Leah Tams. You must click on the square in upper right in order to see the legend.

The green are Huron locations, the purple are French outposts, the orange are the Dutch and the blue is Ashuelot (Keene, NH), from which vantage point I consider this story. What I wasn’t able to put on this map is the Iroquois nation, the Mahicans, and the Sokoki, so I have to work on that. The Iroquois wanted all native New England to sell furs to them, which they would then sell to highest bidder among the Europeans. The French refused the Huron permission to enter into that agreement, so the Iroquois destroyed the Huron, whose remnants fled to Quebec to seek refuge with the French (that’s why one market is green and purple). I made a timeline to go with the map above.

Using Storymap JS by Knightlab: But it turns out there was a tool that would have permitted me to integrate the map and the narrative more directly, called Storymap. Since Storymap is made by the same outfit that made the Timeline JS software, it was not too difficult for me to learn to use it. I watched a tutorial here, and then I made this below. The problem is it comes out stacked and narrow, while it is supposed to open like a book. The solution was to put the Storymap on a PAGE rather than a POST (you are reading a POST). To see how that fixed the situation, look here.

Source for the historical content here discussed is:

Peter A. Thomas (1990). In the Maelstrom of Change: the Indian trade and cultural process in the Middle Connecticut River Valley, 1635 to 1665. New York: Garland Publshing, pp. 204-209.