Legal Disputes

Despite the stories that exist throughout our country about Native land transfer–the ones that claim at some point that natives just vanished from their ancestral lands, freeing the land for European settlers–there are plenty of legal disputes in which Native people, including the Senecas, are attempting to reclaim their land after unjust practices were used to push the natives off their land. Though it may seem like the treaties that were signed two centuries ago do not bear any weight on the lives of native people today, that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

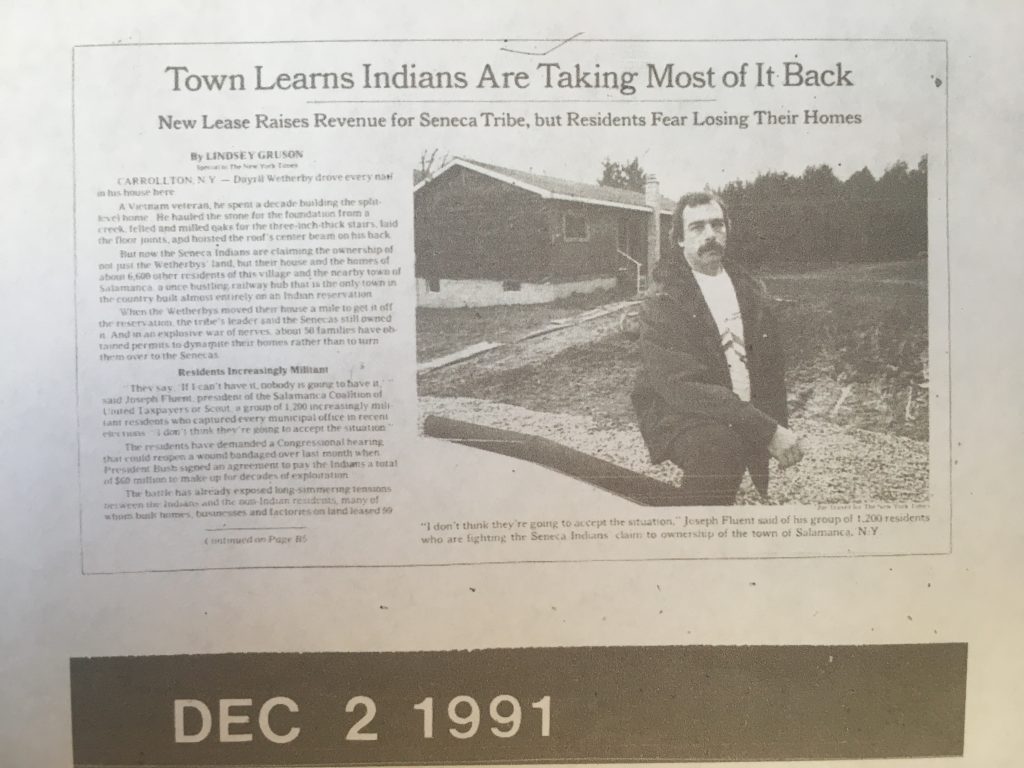

The New York Times article above, from December 2, 1991 describes one such dispute in which the Senecas in Salamanca, New York, were trying to reclaim the land that was owed to them after a 99 year lease (signed in 1891) was up. Relations between the people living in the town, including many Vietnam veterans, and the natives grew increasingly militant as the homeowners in the town even went so far as to get permits allowing them to “dynamite their homes.”

The “Seneca Nation Settlement Act of 1990” was a bill the Senecas sent to the U.S. House of Representatives on July 25, 1990. The bill concerns mainly the city of Salamanca which lies on tribal lands through a historically illegal lease. In the mid-nineteenth century, many railroads obtained grants or leases of right of way through Allegany Reservation without Federal authorization or approval. Subsequently, Reservation lands were leased to railroad employees, people associated with railroads, and farmers and city residents in general—noting none had received Federal authorization or approval.

Upon the courts ruling the leases invalid, Congress enacted the Act of February 19, 1875, which confirmed current leases of the Reservation, authorized further leasing by the Seneca Nation for a renewable twelve year period. However, the Act of September 1890 amended the Act of 1875 to change the renewal to “not exceeding ninety-nine years.”

As a result of the Federal government’s Act, Seneca Nation has suffered tremendous economic loss due to these 99 year long leases that should never have existed from the get-go. The bill demands financial compensation from the government and control over the current Salamanca leases which still rest on Reservation lands.

The author of the article, Lindsay Gruson, writes, “Then in 1892 tribal leaders were reportedly plied with liquor and coerced into signing a 99-year-agreement that all sides now agree was unjust. Negotiations to renew the lease, which expired Feb. 19, sputtered for a decade, creating uncertainty that accelerated the town’s decline.”

As these veterans and other homeowners built their homes and their lives in these homes, the natives were pushed to the outskirts of the town where they lived in extreme poverty.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. To Provide for the Renegotiation of Certain Leases of the Seneca Nation: Hearing Before the Committee On Interior And Insular Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred First Congress, Second Session On H.R. 5367 … Hearing Held In Washington, DC, September 13, 1990. Washington: U.S. G.P.O. , 1991.

See also, the NYT article, “Tribal Shootout: Rival Factions Behind Conflict,” by John Kifner.

It’s clear from this example that the Senecas waited for this 99-year lease to expire, and they have dealt with the consequences of that lease in real, tangible ways. And at the point that the lease was up, it’s clear that the Senecas were in the right as they tried to reclaim what was owed to them.